Tri Rail Palm Beach Gardens

| Tri-Rail | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | South Florida Regional Transportation Authority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Greater Miami | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini | Miami Intermodal Center Mangonia Park | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 18 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Commuter rail | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Herzog Transit Services | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Daily ridership | 10,200 (weekdays, Q4 2021)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ridership | 2,800,100 (2021)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | January 9, 1989 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 73.4 miles (118.1 km) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Character | At-grade | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft8+ 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating speed | 79 miles per hour (127 km/h) ~38 miles per hour (61 km/h) overall average | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tri-Rail (reporting mark TRCX) is a commuter rail line linking Miami, Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach in Florida, United States. The Tri prefix in the name refers to the three counties served by the railroad: Palm Beach, Broward, and Miami-Dade.[2] Tri-Rail is managed by the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority (SFRTA) along CSX Transportation's former Miami Subdivision,[3] [4] the line is now wholly owned by the Florida DOT. The 70.9-mile-long (114.1 km) system has 18 stations along the Southeast Florida coast, and connects directly to Amtrak at numerous stations, and to Metrorail at the Tri-Rail and Metrorail Transfer station and at Miami Intermodal Center.

In 2021, the line had a ridership of 2,800,100, or about 10,200 per day as of the fourth quarter of 2021.

A second Tri-Rail line on the Florida East Coast Railway corridor, dubbed the "Coastal Link", has been proposed. The line would operate between Toney Penna station in Jupiter and MiamiCentral in Downtown Miami, and add commuter rail service between the downtown areas of cities between West Palm Beach and Miami. Combined with the existing Tri-Rail line, the Tri-Rail system would have a daily passenger ridership of almost 30,000; or approximately 9 million passengers per annum, doubling Tri-Rail's current ridership.

History [edit]

1920s: Seaboard-All Florida Railway [edit]

The line on which Tri-Rail operates was built by the Seaboard-All Florida Railway (a subsidiary of the Seaboard Air Line Railroad) for intercity passenger rail service in the early 1920s. The line was inaugurated on January 7, 1927. Intercity rail service by Seaboard operated the Orange Blossom Special service from New York City until 1953. Amtrak continues to offer passenger rail service with the Silver Star and Silver Meteor trains from New York City. Today, the original 1920s Seaboard stations are used by Tri-Rail for service at West Palm Beach, Deerfield Beach, Fort Lauderdale, Hollywood. Though no longer in use, the Seaboard stations at Delray Beach, Opa-locka and Hialeah are still standing.

1980-1990s: Planning and inauguration [edit]

Planning for a new commuter rail line began in 1983, and building the organization began in 1986. The current system was formed by the Florida Department of Transportation and began operation January 9, 1989, to provide temporary commuter rail service while construction crews widened Interstate 95 and the parallel Florida's Turnpike.[5] [6] Tri-Rail was free from opening until May 1, 1990, at which time the fare became $4 round trip.[7]

Due to higher than expected ridership, FDOT made Tri-Rail a permanent service, adding more trains and stations in the process.[ citation needed ] Line extensions have enabled Tri-Rail to serve all three South Florida international airports: Miami International Airport, Fort Lauderdale–Hollywood International Airport and Palm Beach International Airport. The state's original plan was to use the more urban Florida East Coast Railway (FEC) line, but FEC declined the offer as it wanted freight to be their top priority.[8] In 1998, the initial 67-mile-long (108 km) route was extended north from the West Palm Beach station to the Mangonia Park, and south from Hialeah Market to Miami Airport (at an earlier station on the site of the current station). Construction of the extensions began in 1996; which added nearly 4 miles (6.4 km) to the system.

2000s: New stations, more service [edit]

Boca Raton's Tri-Rail station, an example of the mid-2000s rebuilt that includes double track platforms and a pedestrian overpass

In the early 2000s, Tri-Rail received a budget of $84.8 million[ clarification needed ] for double tracking, building extensions, improving stations, establishing a headquarters, and linking to buses.[9]

In 2002, Tri-Rail began to upgrade its grade crossings to include raised medians and/or four quadrant gates to prevent cars from driving around them in an attempt to beat trains. This decreases accidents and allows the cities they run through to petition for them not to use their whistle between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m.[ citation needed ] They also decreased headways to 20 minutes during rush hours.[10]

The Pompano Beach station-slated for rebuild-was not renovated or rebuilt during Tri-Rail's double-tracking but was redone later in the 2010s.

In 2007, a project to upgrade the full length of the line from Mangonia Park to Miami Airport with double track was completed with the opening of a high-level fixed bridge over the New River near Fort Lauderdale. During the 2000s, most of the stations were completely rebuilt to accommodate for double-tracking and include dual platforms, elevators, pedestrian bridges over the tracks, large roofs over the platforms, and better facilities.

In March 2006, Tri-Rail went from 30 passenger trains a day to 40 trains; the completion of the New River rail bridge, the double-tracking project, and the addition of a second Colorado Railcar diesel multiple unit (DMU) ushered in sweeping changes to Tri-Rail's operational timetables. Tri-Rail added several more trains during peak weekday commuting hours in June 2007, increasing to the current 50 trains per day, as well as increasing weekend service.[11] During "rush-hour," trains ran every twenty to thirty minutes rather than the previous schedule of every hour. This change comes at quite a fortuitous time in Tri-Rail's operation history. With gasoline prices at record highs—particularly in South Florida's sprawling metropolis—Tri-Rail saw a double-digit percentage increase in ridership in mid-2007.[ citation needed ] By 2009, annual ridership had reached about 4.2 million passengers.[12] This was also the time during which work was being done on I-95 to add the express lanes from the Golden Glades Interchange to the Airport Expressway near downtown Miami.[13] In 2007, Veolia Transport commenced operating the Tri-Rail service under a contract that ran until June 2017.[14]

2009–present: Growth, Airport Station and Coastal Link [edit]

In 2009, Tri-Rail service was nearly cut drastically, with the threat of being shut down altogether by 2011,[15] even as ridership was at a record high, as Palm Beach County withheld its funding of the system and looked to cut its funding from $4.1 million to $1.6 million per year. This would mean that Broward and Miami-Dade counties would also have had to cut their support to $1.6 million each to match. The state, which was also running a budget shortfall and did not pass a rental car tax increase to help fund Tri-Rail, would have had to cut its support as well. This would have caused an immediate cut from 50 to 30 daily trains and a complete cutting weekend service, followed by additional cuts and possible shut down two years later.[16] Schedules were decreased slightly, but service was never cut altogether, as dedicated federal funding was attained through the $2.5 million grant as part of the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act of 2009.

After a 25% fare increase in mid-2009, annual ridership dropped by 15% (about 600,000) in 2010.[17] However, in 2011, Tri-Rail again saw increasing ridership due to sustained high gas prices, averaging about 14,500 riders per weekday by the end of year. Throughout the year, ridership increased at a rate of about 11% per month, paired with a decline in automobile travel [18] and an increase in employment, with 285 companies and 2,829 individuals joining in the discount program.[19]

In 2011, the dilapidated Pompano Beach station received a $5.7 million federal grant, to be redone as a "green station," generating more than 100% of its energy demand through solar power, with the excess to be sent to the grid or stored for nighttime lighting. Construction started in spring 2012 with the station remaining open during construction.[20] The crossing of Race Track Road and the Tri-Rail line near the Pompano Beach station, rough for several years, was also repaired in 2012.[21]

Total ridership on the system fully recovered to earlier high levels in fiscal year 2013, to 4.2 million.[17] Tri-Rail wants to double ridership by 2021 to 30,000 daily riders by building the Coastal Link.[22]

In April 2015, Miami Airport station opened at the Miami Intermodal Center, once again connecting Tri-Rail directly with the Miami International Airport for the first time since the original Miami Airport station closed in 2011. This new station has connections to MIA Mover (providing a direct link to the airport), Metrorail, Metrobus and Greyhound. After extensive delays, Amtrak has yet to move its operations from its current station.[23] This new station was under construction since 2009, with a September 2011 closure of the original Miami Airport station to allow for construction of the new station.[24]

On January 27, 2017, the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority board voted to award Herzog Transit Services a $511 million, 10-year contract to operate Tri-Rail beginning in July 2017.[25] The board disqualified the other five bidders (Amtrak, Bombardier, First Transit, SNC-Lavalin Rail & Transit and incumbent operator Transdev), stating that they had all submitted "conditional" prices despite the request for proposals mandating that the bid price be final.[25] The other five losing bidders all protested the contract, with Transdev, Bombardier, and First Transit jointly requesting a court injunction to prevent it from being awarded.[25]

Extensions and upgrades [edit]

| Proposed Tri-Rail Coastal Link | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Boca Raton Glades Road station [edit]

In early 2012, it was announced that a second Tri-Rail station in Boca Raton was once again being considered at the busy intersection of Glades Road (S.R. 808) and Military Trail (S.R. 809), near Town Center Mall, Florida Atlantic University and large office parks. A station was proposed for this location in the early 2000s while many other stations were being renovated. Boca Raton station near Yamato Road (S.R. 794) is the busiest station in the system[26] as of 2014, with 1,600 riders a day,[27] surpassing the Tri-Rail and Metrorail transfer station in Miami-Dade County. For this reason, and the fact that Glades Road is considered the most congested road in the county, an infill station there has been long considered.[28] As of 2021[update], the station was not under construction.

Downtown Miami & Coastal Link (FEC line service) [edit]

In the 2025 and 2030 long-range transportation plans, Tri-Rail has envisioned moving to or adding service on the Florida East Coast Railway (FEC) corridor, which runs parallel to U.S. 1 (Biscayne Boulevard/Brickell Avenue) in Miami-Dade County, and Federal Highway in Broward and Palm Beach counties). This corridor will provide more opportunities for pedestrian travel from stations to end destinations than does the current South Florida Rail Corridor, which must rely almost exclusively on shuttle buses for passenger distribution. Tri-Rail officials project that the project would cost about $2.5 billion and that 59,000 people per day would ride it,[8] The FEC, which denied the state's request to use the line for commuter rail in the 1980s, under new ownership has now[ when? ] stated that it is willing to allow the use of the 85-mile-long (137 km) segment of track between downtown Miami and Jupiter for passenger trains.[8]

Tri-Rail service on the FEC line would bring stations to Downtown Miami's transit hub, Government Center station via MiamiCentral, as well as service in Midtown Miami/Miami Design District, Upper East Side/Miami Shores, North Miami, North Miami Beach/Aventura, Downtown Hollywood, and Downtown Fort Lauderdale, putting it within walking distance of thousands of potential riders. Getting to and from the current stations has been a major detractor of Tri-Rail's convenience since opening.[29] Miami's Downtown Development Authority along with Miami-area politicians are[ when? ] actively lobbying to bring Tri-Rail to the city core.[30]

Track connections between the FEC tracks and the South Florida Rail Corridor are also currently under construction.[ when? ] These connections are mainly for freight connectivity between the two lines, but are planned for future Coastal Link use. The Northwood Connection just north of West Palm Beach will provide a new connection as well as rehabilitating an existing connection. The Iris Connection will connect the SFRC to the FEC's Little River Branch near Hialeah. FDOT is building both connections, which were funded by a federal TIGER grant.[31]

The Coastal Link is planned to begin in phases. The first phase is known as Tri-Rail Downtown Miami Link, which would provide service to MiamiCentral station in Downtown Miami. About half of Tri-Rail's trains would switch to the FEC's Little River Branch on the new Iris Connection south of Metrorail Transfer station and head east to the FEC mainline, where they would turn south and head to downtown Miami. The Downtown Link costs about $69 million[32] and is planned to be operational in 2022.[33]

A later phase would allow Tri-Rail to begin service to Jupiter by having trains switch to the FEC on the new Northwood connection north of West Palm Beach and head north to Jupiter with additional stops in Palm Beach Gardens, Lake Park and Riviera Beach. No official timeframe has been given for this phase.[34]

Miami-Dade County is also working to find funding for service on the FEC from Downtown Miami as far north as Aventura.[35] Construction of an additional track for commuter service would require the approval of Brightline, which owns perpetual rights to operate passenger trains over the corridor.[36]

If the Coastal Link is fully implemented, Tri-Rail would operate in three separate services with a line on the FEC tracks from Jupiter to Downtown Fort Lauderdale, a line on the existing tracks from Mangonia Park to Pompano Beach, and then transition to the FEC tracks and continue to Downtown Miami. Another line would run on the existing tracks from Boca Raton to Miami Airport.[37]

Before full implementation of the Coastal Link service can begin, officials have acknowledged that a new higher rail bridge over the New River in Fort Lauderdale is necessary. The FEC's current low-level drawbridge is unable to handle Tri-Rail service along with Brightline and FEC freight service without negatively affecting vessel traffic on the river since the bridge would need to be lowered quite often. Proposals include a taller bridge or possibly a tunnel under the river.[35]

In 2020, Brightline solicited a proposal to operate a commuter rail service on the FEC, utilizing its exclusive trackage rights for passenger service.[38] [39] Under these plans the city of Miami would support the service operated by Brightline, without direct involvement of Tri-Rail.[40]

Operations [edit]

Tri-Rail shares the South Florida Rail Corridor trackage with Amtrak's Silver Meteor and Silver Star and CSX Transportation's Miami Subdivision. The Florida Department of Transportation purchased the track from CSX in 1989. Under the terms of the agreement, CSX would continue to provide dispatch services and physical plant maintenance for the track and would have exclusive freight trackage rights until certain conditions were met. At midnight on March 29, 2015, CSX handed over dispatching and maintenance to SFRTA (Tri-Rail). While this should have the advantage of giving passenger trains signal priority over freight trains, it was at first wracked with delays.[41]

Tri-Rail participates in the Easy Card regional smartcard-based fare collection system along with Miami-Dade Transit. Purely paper tickets are also available for same-day or weekend use. A paper ticket or an EASY Card with a paper-based transfer receipt (created after a confirmed trip is completed) can be used to obtain transfer discounts when transferring to Broward County Transit as well as Palm Tran. Only Easy Cards may be used to obtain a transfer discount when transferring to Miami-Dade Transit.[42] [43] [44]

Due to the route's success, the Silver Meteor and Silver Star do not allow local travel between West Palm Beach and Miami. The two trains only stop to discharge passengers southbound and receive passengers northbound.

Fares and services [edit]

Tri-Rail fare is divided into six zones for 24-hour passes, ranging from $2.50 to $11.55, with fare calculated by the number of zones traveled through, and whether it is one-way or round trip. On weekends, a $5 all-day pass good for all zones is available, though trains run hourly headways. For frequent use, Tri-Rail offers a $100 monthly pass (good for Tri-Rail only) and a $145 regional monthly pass good on Tri-Rail, Metrorail, and Metrobus. Discount fares are available for senior citizens, the disabled, students, and children under 12.[45] Certain businesses allow their employees to register for the Employer Discount Program, which reduces their fares by 25%.[11] Free parking is available at all Tri-Rail stations.[46] On weekdays, 50 train trips are made in all, with 25 in each direction, while on weekends only 30 trips, 15 north and 15 south, are made in all, with 1-hour headways between each train. While Tri-Rail peaks at speeds of 79 miles per hour (127 km/h), it can be extracted from the timetable and the distance of the line that its overall average speed is approximately 38 miles per hour (61 km/h).

Revenue and expense [edit]

For fiscal year 2010, train revenue was approximately $10.3 million.[47] Total operating expenses for fiscal year 2010, including depreciation expense, were approximately $86.9 million. Expenses increased by approximately $14.9 million or 20.7% when compared to fiscal year 2009.[47] 2010 was a low year for ridership after the economy crashed and there were service cuts. By 2015, ridership was about 25% higher.[48] By 2018, fare revenue was budgeted at $13.4 million, whereas operating expense was $119.8 million.[49]

Travel direction [edit]

The line has no turn around point so all trains will face one direction at all times. Locomotives will always face south. For this reason, Dual Operation Passenger Cabs are located on the opposite side of the train facing north. Trains will travel north in reverse and south forwards.

Stations [edit]

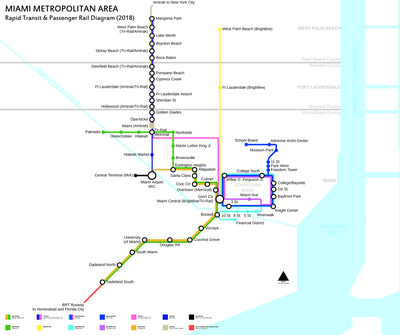

Schematic of rapid transit and passenger rail service in the Miami area in 2018. Tri-Rail's Downtown Miami Link (shown in pink) is expected to be operational in 2022.

A typical station contains two tracks and two side platforms connected by an overpass. Most stations have large parking lots, however, some, like West Palm Beach and Hollywood have a limited number of spaces, most of which are reserved for Amtrak travelers.

| Location | Zone | Station | Time to Pompano Beach | Year opened | Connections |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mangonia Park | 1 | Mangonia Park | 48 min | 1998 | |

| West Palm Beach | West Palm Beach | 42 min | 1925 |

| |

| Lake Worth | Lake Worth | 33 min | 1989 | | |

| Boynton Beach | 2 | Boynton Beach | 28 min | | |

| Delray Beach | Delray Beach | 19 min | 1991 |

| |

| Boca Raton | 3 | Boca Raton | 13 min | 1989 |

|

| Deerfield Beach | Deerfield Beach | 6 min | 1926 |

| |

| Pompano Beach | Pompano Beach | – | 1989 | | |

| Fort Lauderdale | 4 | Cypress Creek | 8 min | | |

| Fort Lauderdale | 15 min | 1927 |

| ||

| Dania Beach | 5 | Fort Lauderdale Airport | 22 min | 2000 |

|

| Hollywood | Sheridan Street | 26 min | 1996 |

| |

| Hollywood | 30 min | 1928 |

| ||

| Miami-Dade | 6 | Golden Glades | 39 min | 1989 |

|

| Opa-locka | Opa-locka | 45 min | 1927 |

| |

| Hialeah | Metrorail Transfer | 52 min | 1989 |

| |

| Hialeah Market | 58 min | | |||

| Miami | Miami Airport | 64 min | 2012 |

| |

| Downtown Miami | 2022[50] |

|

Ridership [edit]

Annual ridership averages

| Date | Passengers[51] [52] Annual total | % Change | Passengers Weekday average |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 2,481,200 | - | N/A |

| 1996 | 2,301,400 | -7.2% | 7,500 |

| 1997 | 2,377,700 | +3.3% | 8,000 |

| 1998 | 2,215,600 | -6.8% | 7,200 |

| 1999 | 2,180,000 | +1.6% | 7,300 |

| 2000 | 2,397,900 | +10.0% | 8,700 |

| 2001 | 2,543,604 | +6.1% | 8,500 |

| 2002 | 2,629,400 | +3.4% | 9,200 |

| 2003 | 2,755,300 | +4.8% | 9,200 |

| 2004 | 2,814,800 | +2.2% | 9,700 |

| 2005 | 2,619,900 | -6.9% | 8,500 |

| 2006 | 3,177,000 | +21.3% | 11,600 |

| 2007 | 3,502,500 | +10.2% | 12,600 |

| 2008 | 4,303,600 | +22.9% | 14,800 |

| 2009 | 3,789,700 | -11.9% | 12,400 |

| 2010 | 3,645,000 | -3.8% | 12,300 |

| 2011 | 3,947,900 | +8.3% | 13,300 |

| 2012 | 4,070,700 | +3.1% | 14,300 |

| 2013 | 4,350,782 | +6.9% | 14,800 |

| 2014 | 4,389,600 | +1.0% | 14,400 |

| 2015 | 4,292,705 | -1.0% | 13,900 |

| 2016 | 4,240,699[53] | -1.0% | 13,900 |

| 2017 | 4,287,400[54] | +1.1% | 13,900 |

| 2018 | 4,413,900[55] | +2.9% | 13,900 |

| 2019 | 4,505,100[56] | +2.0% | 13,900 |

| 2020 | 2,204,500 | -51.1% | 6,400 |

Ridership records [edit]

Tri-Rail posted its highest-paid daily ridership in the commuter-rail system's 24-year history on June 24, 2013. It transported 19,060 people, many of whom attended a "victory parade" for the Miami Heat, which won the 2013 National Basketball Association championship. Most trains operated at or near capacity, SFTRA officials said in a press release. Special four-car sets were operated to accommodate the anticipated overflow crowd.[57]

Previous Miami Heat victory parades resulted in high ridership counts for Tri-Rail, as well. On June 23, 2006, Tri-Rail transported 18,613 riders; and on June 25, 2012, the agency carried 18,355 passengers. In 2019, TriRail reached its highest annual ridership with 4.5 million riders.[56]

Rolling stock [edit]

Locomotives [edit]

The service began with five Morrison-Knudsen F40PHL-2 diesel locomotives. Tri-Rail later took delivery of three MotivePower F40PH-2C locomotives and two ex-Amtrak EMD F40PHs (Now upgraded to 3C specifications and electronics). In 2006, six EMD GP49 locomotives were acquired from Norfolk Southern and were rebuilt by Mid America Car Company to the designation GP49H-3.[58]

On October 29, 2008, the Tri-Rail switched to biodiesel fuel with a goal of a 99-percent blend, when available.[59]

On February 25, 2011, Tri-Rail announced an order for ten Brookville BL36PH locomotives, with options for 13 more, from the Brookville Equipment Corporation at a cost of $109 million.[60] The purchase was met with criticism by the Florida Chamber of Commerce and state lawmakers, who claimed the bidding process was flawed. Rival bidder MotivePower filed a lawsuit against Tri-Rail, claiming that the bidding process was skewed in Brookville's favour.[60] Tri-Rail later added two more BL36PH locomotives to the order for a total of 12. As of 2015, all locomotives have been delivered and are used in regular service, allowing the F40PHL-2, F40PH-2C, and F40PH locomotives to be retired. However, in July 2018, all the F40PH-2C and F40PH locomotives were sent up to Progress Rail in Georgia to be rebuilt and returned to service for use on the Coastal Link. They were returned from August 2020 to January 2021, and have been put back in service.

-

M-K F40PHL-2 locomotive in Hollywood

-

EMD M-K F40PH-2C locomotive at West Palm Beach

-

EMD F40PH locomotive at Miami Intermodal Center

-

EMD GP49H-3 locomotive at Metrorail Transfer

-

Brookville BL36PH locomotive at the Miami Intermodal Center

-

EMD PRLX F40PH-3C at the Miami Intermodal Center

Passenger cars [edit]

Tri-Rail uses two types of passenger cars. Since the beginning of operations, the system has used 26 Bombardier BiLevel Coaches purchased new from Urban Transportation Development Corporation (even though they were delivered in GO Transit colors, the Tri-Rail cars were purchased new and never used or sold secondhand by GO, only leased by GO for a short period of time), a common model among Canadian and US commuter railroads, 11 with operating cabs and 15 without. Briefly, bi-level rolling stock from Colorado Railcar (4 DMU power coaches and 2 unpowered coaches) was used beginning in 2006.

In 2010, the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority agreed to purchase new rail cars from Hyundai Rotem for $95 million.[61] The first new car was put into service in March 2011. By late 2011, the 12 new locomotives and 24 new passenger cars had not yet been delivered, and the original cars, many over 30 years old, were falling into disrepair. This led to Tri-Rail often running two cars per train instead of three despite increasing ridership, leaving only standing room on many trains during rush hour.[62] By January 2013, all trains were again running with 3 cars, just as most of the Hyundai Rotem rail cars were delivered. In addition to decreased comfort but more reliability, the new cars provide additional safety with front and rear crumple zones designed to absorb energy in a crash.[61]

In 2015, three Bombardier coaches were renovated to include additional bicycle capacity. Cars 1002, 1006, and 1007 had one side of seating removed from the lower levels, which were in turn replaced by bike racks. These trains with special bike cars have the capacity to carry an additional 14 bicycles per train.

-

Tri-Rail cab car 510 arriving at Delray Beach

-

Tri-Rail cab car 501 departing Deerfield Beach

-

Bombardier bi-level coaches in Pompano Beach

-

One of Tri-Rail's bicycle cars, renovated to accommodate 14 bicycles per car

-

Hyundai Rotem trainsets at Miami Airport

-

Hyundai Rotem Cab in Hollywood

-

Hyundai Rotem cab closeup

Diesel multiple units [edit]

In 2003, after receiving a grant from the Florida Department of Transportation, Tri-Rail contracted to purchase two pieces of rolling stock from Colorado Railcar: a self-propelled diesel multiple unit (DMU) prototype control car and unpowered bi-level coach entered regular service with Tri-Rail in October 2006. The new purpose-built railcars are larger than the Bombardier BiLevel Coaches, holding up to 188 passengers, with room for bicycles and luggage. Tri-Rail possessed four DMU control cars and two unpowered trailer cars. One DMU train usually consists of two DMU power cars at each end of a trailer coach (making for two complete DMU+trailer+DMU sets on the system). One trainset was sent to the SunRail Rand Yard in Sanford, FL, months before the system opened, for test purposes on their new commuter line. The trainset was sent back to the CSX Hialeah Yard soon after SunRail began revenue service. As of 2012, all the DMUs and trailers were retired and out of service. They are currently in storage at the Tri-Rail service facility.

-

A pair of DMUs trailing behind EMD GP49 engine 813 in Hialeah Railyard

-

Colorado Railcar interior

Chart [edit]

| Year built | Make and model | Road Nos. | Total built | Total in service | Capacity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locomotives | ||||||

| 1968 (Rebuilt 1988) | M-K EMD F40PHL-2 | 801-805 | 5 | 0 | 3 crew | Rebuilt from CR GP40 locomotives in 1988. Retired in 2015. 802, 803, 805 currently stored and sold to BUGX, two rebuilt into road switchers for the D&SNG. |

| 1992 (Rebuilt 2020–21) | M-K EMD F40PHM-3C | 807-809 | 3 | Previously retired in 2015 (809 ran until February 2016), all were rebuilt, repainted royal blue, and returned in 2020. Entered service again in May 2021. | ||

| 1981 (Rebuilt 2020–21) | EMD F40PHR-3C | 810-811 | 2 | Ex-Amtrak units acquired in 1997. Retired in 2015, rebuilt, repainted royal blue, and returned in 2020–21. Re-entered service in May 2021. | ||

| 1980 (Rebuilt 2006) | EMD GP49H-3 | 812-817 | 6 | 4 | Ex-NS GP49s. Locomotives were rebuilt and reclassified as GP49H-3 in 2006. Only 812, 815, 816, and 817 are still in service. 813 was retired in a January 2016 incident. 814 was retired and is now being used as a parts source. 816 suffered fire damage in August 2020; it was repaired and returned to service in March 2022. | |

| 2013–15 | Brookville BL36PH | 818-829 | 12 | Delivered from 2013 to 2015. All are in service. | ||

| Passenger coaches and cab cars | ||||||

| 1987 | UTDC Bi-Level Cab Car | 501-506 | 6 | 136 and 3 crew | Single-window half-width cab cars. 501 was involved in a 2016 derailment, and returned to service on May 31, 2022. | |

| 1987–1990 | UTDC Bi-Level Passenger Coach | 1001–1015 | 15 | 13 | 142 (trailer cars), 128 (bicycle cars) | Most are now bicycle cars. 1001 and 1009 are out of service following a 2016 derailment. |

| 1996 | Bombardier Bi-Level Cab Car | 507-511 | 5 | 3 | 136 and 3 crew | Full-width cab cars with two front windows and washroom at B end of car. 509 is out of service following a 2019 collision, and 510 is permanently retired and scrapped following a 2016 collision with a garbage truck. |

| 2010–11 | Hyundai Rotem Cab Car | 512-521 | 10 | 140 and 3 crew | In service since 2013. Briefly banned from leading following the failure of an inspection in 2019. | |

| Hyundai Rotem Passenger Coach | 1101–1114 | 14 | 146 | Entered service from 2011 to 2013, and all are currently active. | ||

| Diesel multiple units | ||||||

| 2002 | Colorado Railcar Single-Level DMU Demo | 702 | 1 | 0 | 73 and 3 crew | Formerly Colorado Railcar #2002; brought by Tri-Rail, repainted, and given a new number in 2004. It is now stored in Pueblo, Colorado. |

| 2005–09 | Colorado Railcar Bi-Level DMU | 703-706 | 4 | 165 and 3 crew | All were taken out of service in 2012 due to reliability issues, and are currently in storage. | |

| 2005–07 | Colorado Railcar Bi-Level Trailer Coach | 7001-7002 | 2 | 182 | Large double-decker coaches that usually transited with two DMUs. Currently out of service and in storage. | |

Accidents and incidents [edit]

On January 4, 2016, a passenger train collided with a garbage truck which had broken down on a grade crossing at Lake Worth station and was derailed. Twenty-two people were injured.[63] This marked the first derailment in almost 27 years of operation.

On January 28, 2016, Tri-Rail suffered their second derailment in Pompano Beach, after a train hit debris on the tracks between the Cypress Creek and Pompano Beach stations. This section of track is also where Tri-Rail is allowed to go its fastest speed, 79 MPH. One injury was reported and GP49H-3 locomotive #813 and a Bombardier BiLevel Coach directly behind it came off the rail.[64]

On October 25, 2019, a northbound Tri-Rail train led by Bombardier cabcar #509 hit a semitruck in Oakland Park. Several people were injured, and cabcar 509 was sidelined after the incident.[65]

On August 19, 2020 at Deerfield Beach, GP49H-3 locomotive 816 was caught on fire and its passengers from the train were safely evacuated. No injuries were reported.

-

Derailed Tri-Rail cars in Lake Worth on January 4, 2016

-

View of the train and garbage truck it struck in Lake Worth

-

Wrecked crossing signals at the site of the Lake Worth accident

See also [edit]

- Metrorail (Miami)

- Metromover

- SunRail

- Transportation in South Florida

- List of Florida railroads

- List of United States commuter rail systems by ridership

- Commuter rail in North America

References [edit]

- ^ a b "Transit Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2021" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. March 10, 2022. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- ^ "Tri-Rail Train Schedule". 9 July 1997. Archived from the original on 9 July 1997. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "MI-Miami Sub – The RadioReference Wiki". wiki.radioreference.com . Retrieved 2020-05-22 .

- ^ Downing, R.R. (January 1, 2005). "CSX Transportation|Jacksonville Division Timetable No. 4" (PDF). multimodalways.org . Retrieved 2020-05-22 .

- ^ 3,000 a day ride Tri-Rail trains Railway Age February 1989 page 24

- ^ "TRI-RAIL South Florida's Commuter Rail System". GetCruising.com . Retrieved 2011-11-10 .

- ^ "Tri-Rail's hardtimes WTVJ 1990". WJTV/YouTube. Retrieved 2011-12-02 .

- ^ a b c "Officials seek public input on new transit option along FEC tracks". Sun-Sentinel. September 16, 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-09-21. Retrieved 2011-11-14 .

- ^ Gibson, William E. (April 10, 2001). "Tri-Rail gets boost in U.S. budget shortfall: Bush's budget proposal leaves Everglades projects out $58 million". Sun-Sentinel . Retrieved 2011-12-02 .

- ^ Turnbell, Michael (June 20, 2002). "Tri-rail Upgrade To Speed Service". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2014-02-04. Retrieved 2011-12-01 .

- ^ a b "Now we can get you to work faster..." (PDF). SFRTA. Retrieved 2012-01-12 .

- ^ "Gov. Rick Scott raps Tri-Rail while rejecting high-speed rail funding". Politifact. 2011-03-01. Retrieved 2018-12-29 .

- ^ "I-95 express lane construction comes to Broward starting Nov. 28". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2013-02-03. Retrieved 2011-11-23 .

- ^ "Veolia gets Tri-Rail contract extension". Railway Age. August 30, 2013.

- ^ "We can't let Tri-Rail close!". CNN. June 7, 2009. Archived from the original on April 21, 2010. Retrieved 2011-11-28 .

- ^ Polansky, Risa (April 2, 2009). "Tri-Rail may be forced to cut half its weekday routes, eliminate weekend service". Miami Today News. Retrieved 2011-11-28 .

- ^ a b "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2013" (PDF). South Florida Regional Transportation Authority. December 12, 2013. Retrieved 2014-06-12 .

- ^ Salisbury, Susan (December 9, 2011). "Driving on the decline as gas prices remain above $3 a gallon". Palm Beach Post . Retrieved 2011-12-09 .

- ^ Turnbell, Michael (January 12, 2012). "Tri-Rail's ridership soars in 2011". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved 2012-01-12 .

- ^ Turnbell, Michael (November 27, 2011). "New Pompano Beach Tri-Rail station will be solar-powered". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2011-11-28 .

- ^ Turnbell, Michael (November 25, 2011). "Rough railroad crossing in Pompano Beach irks jostled drivers". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2013-07-23. Retrieved 2011-12-01 .

- ^ Smiley, David (11 April 2015). "Push to build Miami Tri-Rail station driven by desire as much as data". Miami Herald . Retrieved 2015-04-14 .

- ^ "The trains are too long. The platform is too short. Bad news for the new station". Miami Herald. January 29, 2017. Retrieved 2017-01-30 .

- ^ Turnbell, Michael (April 5, 2015). "Tri-Rail opens Miami airport station". Sun-Sentinel . Retrieved 2015-04-05 .

- ^ a b c "Massive Tri-Rail deal approved after bids tossed, warnings issued". Miami Herald. January 27, 2017. Retrieved 2017-01-30 .

- ^ Streeter, Angel (January 4, 2011). "Second Tri-Rail station in Boca Raton proposed". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved 2011-01-04 .

- ^ Latzman, Philip D. (April 7, 2015). "As ridership increases, Boca Raton embraces train travel". Sun-Sentinel . Retrieved 2016-08-19 .

- ^ Streeter, Angel (May 11, 2014). "New Boca Raton Tri-Rail station on the horizon". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2017-07-01. Retrieved 2016-08-19 .

- ^ "Tri-Rail Open WJTV". WJTV/YouTube. 1989. Retrieved 2011-11-27 .

- ^ "Miami Downtown Development Authority hashing out plans to bring Tri-Rail downtown". Miami Today News. October 29, 2009. Retrieved 2011-02-27 .

- ^ "S. FL Freight and Passenger Rail Enhancement Project". Florida Department of Transportation . Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ "Tri-Rail Downtown Miami Link Service". Tri Rail. Southern Florida Regional Transportation Authority. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "Tri-Rail Downtown Miami Link Service". Tri Rail. South Florida Regional Transportation Authority. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

Downtown Miami Link is anticipated to begin service in 2022.

- ^ "Tri-Rail Coastal Link Project Update" (PDF). Tri-Rail Coastal Link . Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ a b Barszewski, Larry. "Difficult track ahead for coastal commuter rail". Sun Sentinel. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ Lyons, David (8 November 2019). "Waiting for Tri-Rail to run through downtowns? Don't hold your breath". Sun Sentinel . Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ "Tri-Rail Coastal Link System Map" (PDF). Tri-Rail Coastal Link . Retrieved 2015-02-18 .

- ^ "Brightline in talks with Miami-Dade to run commuter-rail line, report says". Progressive Railroading. 29 May 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Price-Williams, Abigail. "Memorandum" (PDF). Miami Dade County . Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ "Brightline close to county deal on commuter tracks. Next up: Fights over stations". Miami Herald. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ Turnbell, Michael (April 6, 2015). "Tri-Rail falters in first week of dispatching". Sun-Sentinel . Retrieved 2015-04-13 .

- ^ "rider_info/fare_information". tri-rail.com. Retrieved 2017-04-07 .

- ^ "rider_info/transfer_info". tri-rail.com . Retrieved 2017-04-07 .

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-16. Retrieved 2012-02-29 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Calculating Your Fare". Tri-Rail. Retrieved 2013-10-28 .

- ^ "Save Money on Holiday Travel by Riding Tri-Rail to Airports Across South Florida". prweb.com . Retrieved 2011-12-04 .

- ^ a b "South Florida Regional Transportation Authority Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2010" (PDF). SFRTA.

- ^ Smiley, David (April 11, 2015). "Push to build Miami Tri-Rail station driven by desire as much as data". Miami Herald . Retrieved 2015-04-12 .

- ^ https://media.tri-rail.com/Files/About/SFRTA/Resources/Financials/Operating/Complete%20PDF%20FY%202019-2020%20Operating%20Budget.pdf[ bare URL PDF ]

- ^ San Juan, Rebecca (August 7, 2018). "Tri-Rail targets third quarter 2019 runs to downtown Miami". Miami Today . Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ "2002-2007 Annual Ridership through March 31, 2007" (PDF). SFRTA. Retrieved 2011-12-11 .

- ^ Kittelson & Associates (August 2007). "Performance Measurement Evaluation" (PDF). SFRTA. Retrieved 2011-12-11 .

- ^ "Annual Update Final Draft" (PDF).

- ^ https://ti.org/pdfs/2017-Q4-Ridership-APTA.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwi6jq_wysbpAhUBvp4KHQ4lAGwQFjAGegQIAhAB&usg=AOvVaw0iP1Ehgb5Wi9FyXE0CHqiA [ dead link ]

- ^ https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/2018-Q4-Ridership-APTA.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjXorbg8MbpAhWLvp4KHSgTDNMQFjACegQIAxAB&usg=AOvVaw3zy8tDw-Nrwdr4s-sREYIM [ dead link ]

- ^ a b https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/2019-Q4-Ridership-APTA.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwiUrpeOkMjpAhWSJzQIHRcmCjQQFjAEegQIBBAK&usg=AOvVaw2Uwd3rFLsZ9LeH_rk_7YT0 [ dead link ]

- ^ "Tri-Rail scores record daily ridership due to Miami Heat parade". SFRTA/Progressive Railroading. June 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-26 .

- ^ Tri-Rail takes on rare GP49s Trains April 2007 page 29

- ^ "South Florida Regional Transportation Authority". Sfrta.fl.gov . Retrieved 2011-02-27 .

- ^ a b "$109 Million Tri-Rail Contract Awarded After Challenge". Sunshine State News. February 25, 2011. Archived from the original on February 27, 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-27 .

- ^ a b Turnbell, Michael (January 5, 2013). "Tri-Rail gets new, safer passenger cars". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2013-07-02. Retrieved 2013-05-09 .

- ^ "Tri-Rail faces more challenges than crowded cars". Sun-Sentinel. December 2, 2011. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved 2011-12-02 .

- ^ Sutton, Scott; Noce, Christina; Sarann, Gabrielle (4 January 2016). "Tri-Rail hits garbage truck in Lake Worth; 22 people suffer minor injuries". WPTV. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 2016-01-05 .

- ^ "Delays expected after Tri-Rail train derailment in Pompano Beach". WSVN-TV – 7NEWS. 2016-01-28. Archived from the original on 2016-01-29. Retrieved 2016-11-16 .

- ^ "Several Injured In Tri-Rail Collision With Semi-Truck In Oakland Park". CBS Miami 4 News. CBS Miami 4. 2019-10-25. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tri-Rail. |

Route map:

KML is from Wikidata

- Official website

- Tri-Rail Coastal Link Study

- South Florida Regional Transportation Authority

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tri-Rail

0 Response to "Tri Rail Palm Beach Gardens"

Publicar un comentario